As tax professionals today, we find ourselves balancing massive potential gains from generative AI against the deeply ingrained structures of a conservative, regulated industry. The tension is palpable: on one hand, practitioners are genuinely intrigued by promises of automating routine data processing, potential respite from overwhelming volume and complexity, and the interesting prospect of uncovering near real-time insights. On the other hand, they operate in the rigid framework of mitigating compliance risks, liability concerns, the inescapable need for human sign-offs, and viewed in many businesses as low-value back-office cost-centers.

A parallel inflection point can be drawn from a time when librarians first introduced barcodes and automated check-out systems, effectively revolutionizing how people perceived library operations (1). Before that shift, manual card catalogs framed the library as a place of methodical, if somewhat slow, exploration; after automation, librarians were able to see their workflows in entirely new ways. This evolution changed not only the speed of checking out books but also the library’s organizational identity: from a static repository to a dynamic, data-driven environment.

This is an inflection point that asks tax professionals to question which parts of their roles can be safely delegated to an AI model.

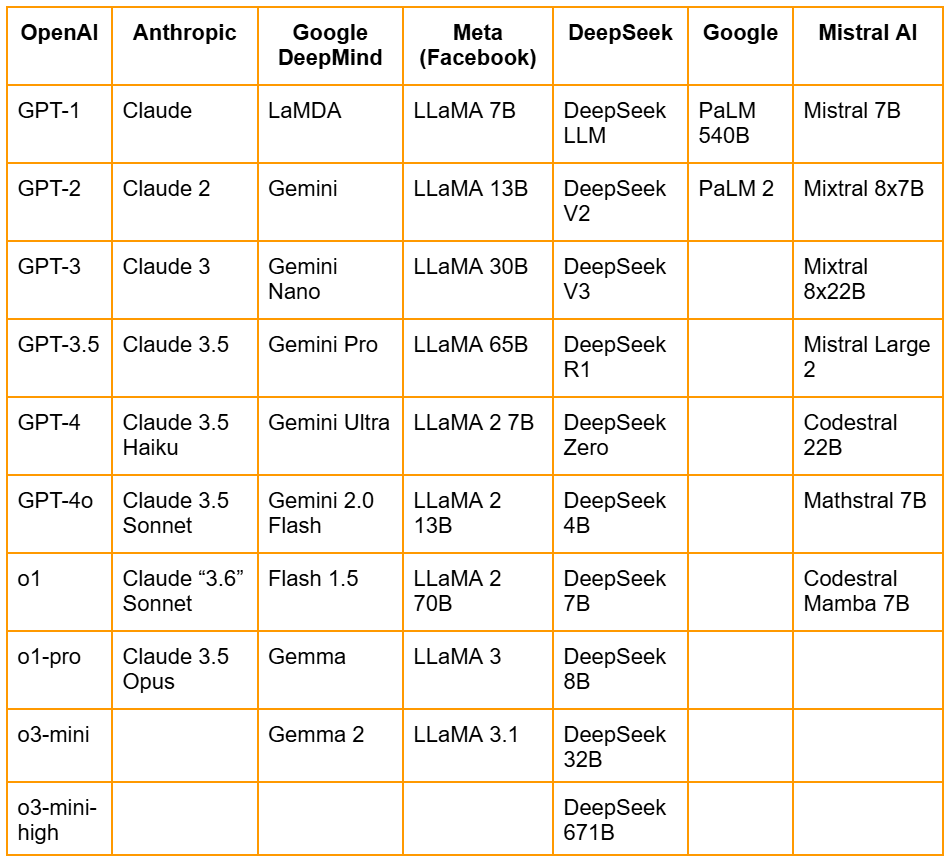

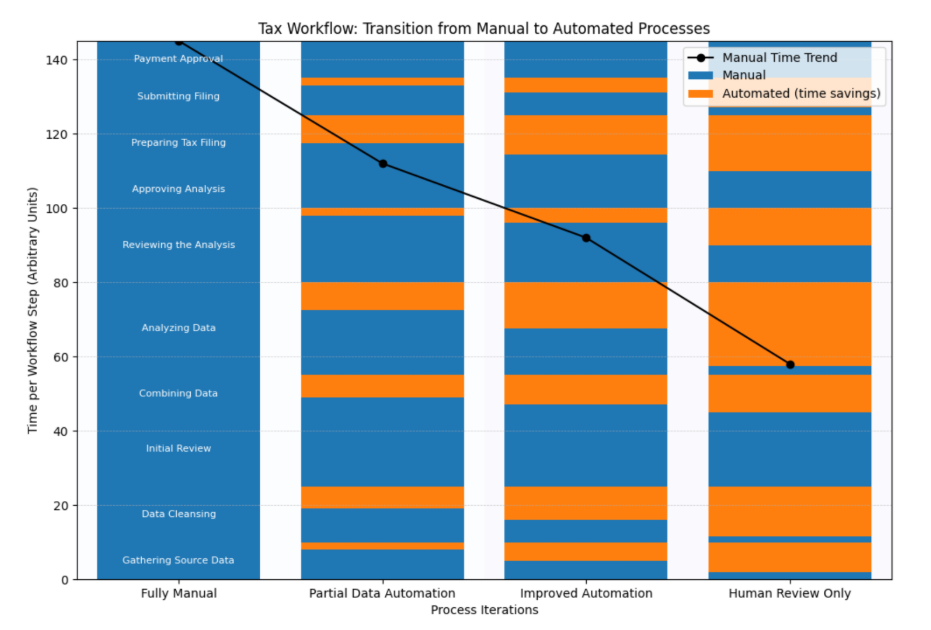

Today we stand at a similar junction. Technological innovations—whether barcoded check-outs in a library or AI-driven scanning of invoices—have historically done more than just speed up tasks. They have reconfigured how entire organizations perceive their purpose, reshaped who does the work, and redefined what skills and processes are needed on a day-to-day basis. Adopting generative AI within tax operations is not just a matter of plugging in a new software tool; it requires a fundamental change in how people will co-work with AI in the design of their workflows. And change is coming (appendix 1).

The pressure to innovate is growing, yet the psychological inertia of a risk averse profession to stepping outside long-standing norms remains a limiting obstacle. We’re at an inflection point that asks tax professionals to question which parts of their roles can be safely delegated to an AI model—and, more importantly, how they might reimagine the very nature of their work to harness these new capabilities effectively.

Historical Parallels: From Punched Cards to Cloud-Based AIS

Our generation is experiencing a tectonic shift for the first time; however, this current wave of AI-driven transformation is not the first time the accounting profession has grappled with disruptive technology. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mechanical calculators, punched-card machines, and specialized billing systems radically altered bookkeeping practices (2). These machines, at the time startlingly innovative, allowed organizations to process transactions faster and more uniformly, paving the way for the modern notion of standardized financial reporting.

As adoption increased, a rift emerged between the role of the bookkeeper and the accountant. Bookkeepers frequently found themselves operating newly invented adding machines, mastering the practicalities of tabulating large volumes of data. Accountants, by contrast, gravitated toward planning, oversight, and more strategic responsibilities—foreshadowing the same kind of role redefinition we see today with AI. We can’t envision the changes with clarity, but the echoes of past professional evolutions suggest our professional oversight will extend to agentic systems, refining our orchestration skills and creating new frameworks to review AI generated output.

History shows that while technology can certainly streamline repetitive tasks, its true impact often lies in reshaping the structure of work and the mindset of those who rely on it.

Fast-forward to today’s finance departments and the rise of electronic accounting information systems (AIS), and one sees how incremental adoption of technology reshaped the entire discipline. A similar pattern is emerging with AI: early AIS research focused heavily on system design while often overlooking the human element (5), and today’s AI hype risks repeating that mistake. The belief that ‘AI can do anything’ may lead to underestimating the critical role of human participation in its successful implementation and use. History shows that while technology can certainly streamline repetitive tasks, its true impact often lies in reshaping the structure of work and the mindset of those who rely on it.

Behavioral and Acceptance Frameworks

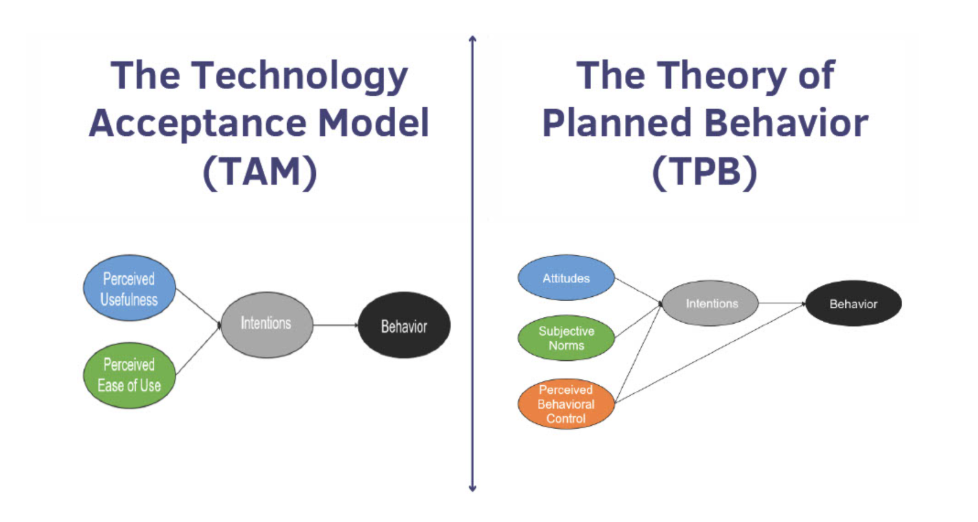

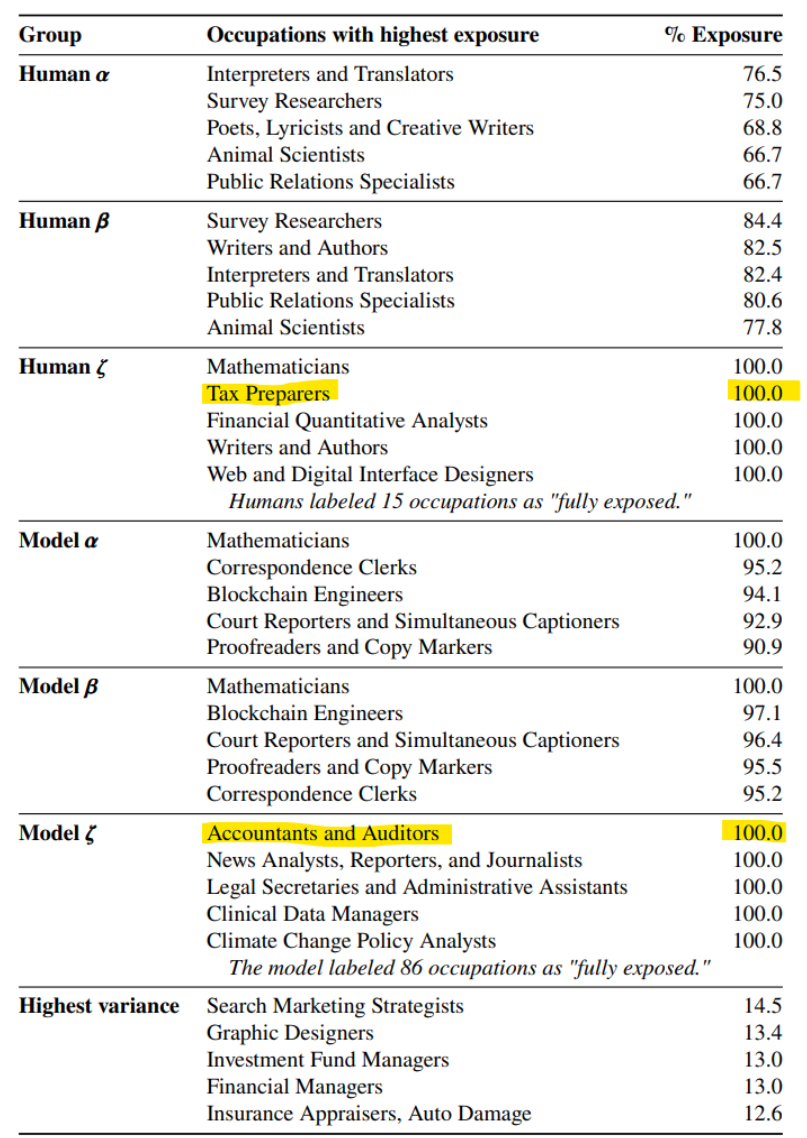

Even the most advanced AI tool will fail to gain traction if end users doubt its reliability or struggle to incorporate it into existing routines. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has long posited that perceived usefulness and ease of use are among the strongest predictors of whether people embrace new systems (3). Although TAM originated in studies of more conventional software applications, its underlying principles remain highly relevant in the context of AI-enabled tax processes. We must see clear, tangible benefits—such as improved accuracy or decreased turnaround time—and the interface itself must fit seamlessly into our established workflows. The current alphabet soup of models’ names further confounds adoption (appendix 2).

…confidence in using AI depends on whether tax professionals feel they have the right training, resources, and support to oversee or override it when necessary.

This connects to the Theory of Planned Behavior, which says that people’s willingness to adopt new technology is influenced by social expectations and their confidence in managing change. In the tax world, expectations come from executive leadership, firm partners, professional bodies, and clients—some embrace AI, while others are deeply skeptical. At the same time, confidence in using AI depends on whether tax professionals feel they have the right training, resources, and support to oversee or override it when necessary. If they don’t feel in control, the risks may seem bigger than the benefits, slowing down adoption.

One of the biggest challenges for tax professionals is truly grasping what really sets generative AI apart from the standard enterprise software we’re accustomed to: its ability to infer and create beyond simple data entry. Its intelligence can accelerate tasks like summarizing complex regulatory documents, its reasoning abilities can augment problem solving exercises, but it can also introduce unpredictable “hallucinations” or errors. These mistakes may stem from user misapplication or the probabilistic nature of AI itself. You can thus see one small example of how workflows must change by adding in more standard and rigorous approaches to verify LLMs’ outputs.

[T]here is no standardized training on maximizing genAI in your workflows…creating a gap between acceptance and true transformation that must be bridged through training tailored and hand-on experience.

To fully realize AI’s benefits, tax professionals must adopt it from the ground up, at the individual level. While organizations will integrate AI into enterprise systems, generative AI isn’t a top-down implementation like an ERP, which enforces standardized workflows. Instead, its success depends on how well individual professionals learn to incorporate it into their daily tasks. Fortunately, tax professionals are already skilled at reviewing others’ work, making the need for human oversight of AI a natural extension of existing practices. However, there is no standardized training for effectively integrating AI into tax workflows. This creates a gap between simple adoption and true transformation—one that must be bridged through tailored training and hands-on experience.

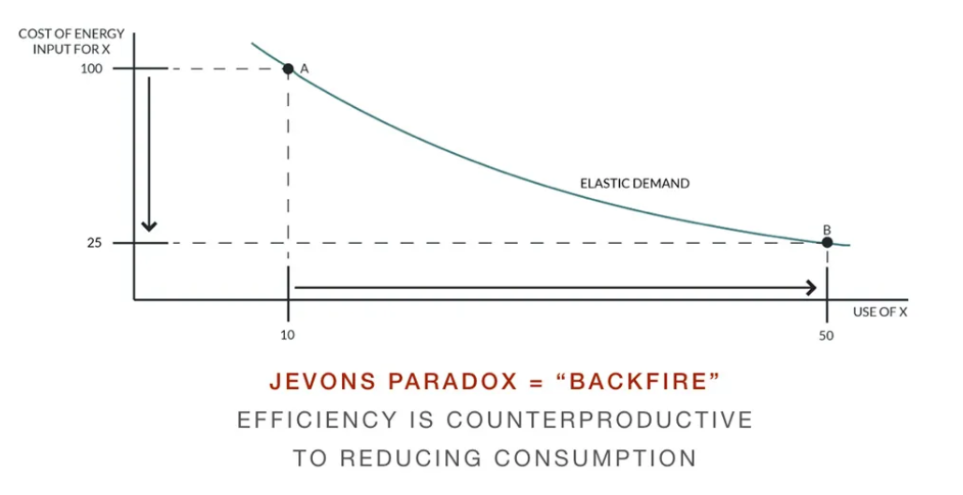

Generative AI Meets Jevons’ Paradox

We should not temper the excitement over how generative AI can automate low-level tasks like data manipulation and sanitization or even more complex functions such as interpreting evolving tax regulations in-house. This repetitive hamster-wheel type activity, without a sense of valuable purpose, is a drain to the quality of our professional lives; however, there lurks a paradox: the more efficiently a resource is used, the greater the overall consumption of that resource can become. This is Jevons’ paradox, and it applies strikingly to the potential use of AI in tax workflows. By reducing the labor and time required to produce critical tax deliverables—be it automating tax provisions or identifying planning opportunities—firms and in-house departments may find themselves handling even more requests, analyses, and last-minute compliance checks than before.

As mundane tasks become cheaper and faster to complete, senior leaders may see new opportunities to expand the scope of what their tax teams can provide. With previous bottlenecks removed and grinding workloads alleviated, this new capacity becomes available for the kind of stimulating and rewarding higher-value work we enjoy; paradoxically prompting a surge in additional tasks.

By reducing the labor and time required to produce critical tax deliverables…firms and in-house departments may find themselves handling even more requests, analyses, and last-minute compliance checks than before.

There are therefore implications for tax professionals’ career trajectories. As repetitive chores shrink, the more strategic, complex tasks balloon. This shift aligns with predictions that AI will free humans to concentrate on “higher-value activities” like business consulting, what-if scenario modelling and more accurate risk management. Yet, if the volume and speed of these higher-order requests keep growing, professionals will feel pressured to juggle a greater number of strategic engagements in the same amount of time. The paradox, then, is that time saved on the front end might translate into accelerated intensity on the back end.

Don’t despair, the upside is clear: properly harnessed, AI can raise the ceiling on what tax departments deliver. But without deliberate planning and resource management, the real payoff—improved effectiveness, not just higher workloads—could remain elusive. The lesson is that generative AI, while truly transformative, must be introduced alongside process governance (reimagining our workflows), measured client or stakeholder expectations, and structured communication loops. Otherwise, you simply shift from a labor bottleneck to a complexity bottleneck, perpetuating the very burdens the technology was meant to ease.

Organizational Bottlenecks: Amdahl’s Law in Practice

While AI-enabled tools may accelerate the preparation of returns or the analysis of large datasets, Amdahl’s law reminds us that a workflow’s overall speed is limited by its slowest component. Within tax engagements, that slowest component is often human-centric—a senior manager’s sign-off, a legal review, or simply the time needed for CFOs and audit committees to digest new findings. Just as the 19th-century introduction of mechanical accounting machines did not eliminate the need for oversight from accountants (2), today’s AI-driven tax departments must navigate the choke points of human judgment and regulatory compliance.

Consider the example of the 2026 in-house tax department adopting AI to automate tasks like real-time data analysis and complex error detection[new ideas]. On paper, these improvements promise near-instant results, especially when combined with the capacity for AI to review multiple data sets simultaneously. In practice, however, each flagged anomaly or newly discovered tax opportunity must still be assessed within the organization’s established sign-off procedures. If compliance teams do not trust the AI’s outputs or if partner-level professionals are unfamiliar with how these algorithms function, critical decisions are delayed pending more thorough manual reviews. At that juncture, the biggest drag on speed is not the technology but the organizational readiness—a classic reflection of Amdahl’s law, where the overall process remains only as fast as the slowest step.

Tax professionals must grasp not just the front-end interface but also the underlying logic driving generative AI’s recommendations, and their own role in shaping the output.

Again, skills and training gaps can also constrain how fast AI is absorbed into the tax function. While managers and executives may perceive generative AI as a “game-changer”, the professionals who handle daily data workflows may not yet feel comfortable trusting machine-driven outputs—or even know how to interpret an AI’s analytical model. Upskilling and reskilling become essential. Tax professionals must grasp not just the front-end interface but also the underlying logic driving generative AI’s recommendations, and their own role in shaping the output. Until enough staff members reach that level of comfort and competence, adoption might stall.

Thus, even as AI technologies scale up certain components of the tax process with breathtaking speed, the “slowest link” principle remains in full effect. For generative AI to deliver net gains—rather than merely accelerating one slice of the workflow—firms and in-house teams must address these inherent constraints.

Practical Pathways for the Next 6 – 12 Months

In moving from concept to action, tax professionals and in-house departments stand to benefit from a targeted, incremental approach toward AI integration. Rather than revamping entire compliance workflows overnight, many organizations are experimenting with pilot programs—small-scale testbeds that concentrate on specific processes such as invoice classification, error spotting, or even AI-facilitated chatbots to handle routine tax inquiries. These focused trials help validate the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) on a small scale, showing staff that generative AI can indeed streamline tasks without compromising accuracy. In a profession where trust and compliance are paramount, it is vital to reinforce that humans remain firmly in the loop, ready to override or refine any AI-driven output.

Another imperative is the simultaneous investment in upskilling and reskilling. Even if only a subset of the workforce acquires in-depth AI expertise, that cadre can become a knowledge hub, sharing best practices to the rest of the team. Slack channels or other collaborative platforms must be leveraged for learning and sharing insights. They should be paired with rewards and incentives to experiment, test and share; ultimately encouraging faster and broader adoption of “what works well”. In effect, the next six months should be about building organizational muscle memory—refining internal processes, clarifying accountability, and ensuring that early wins pave the way for more expansive, long-term transformations.

Anticipating the Two-Year Horizon

Over the next two years, the IMF’s perspective on AI and worker reallocation will likely play out in tax departments as well, with some routine roles at risk while new, more specialized positions (e.g., “AI analyst” or “digital tax strategist”) emerge (4). The tension between the promise of technology and the practicalities of regulatory compliance, data security, and staff training will continue to shape the speed and scope of adoption.

If you’ve made it this far, do not hesitate to reach out to me to discuss how we can work together on your personal or departmental AI adoption journey. As always, much gratitude for having given me your attention as you’ve read along. We’re all in this together, we can help each other.

_______________________________________

References:

- Boell, S. K., & Hoof, F. (2020). Accounting for information infrastructure as medium for organisational change. Accounting History Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/21552851.2020.1713184

- Wooton, C. W., & Kemmerer, B. E. (2007). Emergence of mechanical accounting in the U.S., 1880-1930. Accounting Historians Journal, 34(1), 91-124.

- Quinto, E. J., II. (2022). How Technology Has Changed the Field of Accounting [Master’s thesis, Bridgewater State University]. Virtual Commons – Bridgewater State University. https://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj/558

- Cazzaniga, M., Jaumotte, F., Li, L., Melina, G., Panton, A. J., Pizzinelli, C., Rockall, E., & Tavares, M. M. (2024). Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (IMF Staff Discussion Note No. SDN/2024/001). International Monetary Fund.

- Badua, F. A., & Watkins, A. L. (2011). Too young to have a history? Using data analysis techniques to reveal trends and shifts in the brief history of accounting information systems. Accounting Historians Journal, 38(2), 75-103.

- Tyna Eloundou, Sam Manning, Pamela Mishkin, and Daniel Rock, GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models (OpenAI, August 22, 2023), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.10130

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

An incomplete sample of model names demonstrating the confusion over what models to use, for which tasks, and when. Did you know Open AI model o3-mini high is less capable than o1 and o1-pro for reasoning tasks, but better at writing code?