Why Today’s Automation Lays the Groundwork for Tomorrow’s Agents

I’m learning a dying language when everyone is learning to vibe code. That’s the new frontier of development where you simply describe what you want to an AI in plain English and let it manifest the software. It seems like I’m going in reverse, but there’s a reason.

I’m learning ‘VBA’ – the legacy programming language built into Microsoft Office.

Well, that’s not entirely true, the AI already knows the language, and, frankly, all the code is written by the model itself. Frontier AI labs even admit that their products are now mostly AI-coded.

Boris Cherny (Head of Claude Code at Anthropic): “For me personally, it has been 100% for two+ months now, I don’t even make small edits by hand.”

Roon (OpenAI researcher): “100%, I don’t write code anymore.”

What I’m really doing is orchestrating multiple AIs to build the architecture that automates tax operations. If I accidentally pick up some VBA along the way, that’s just a byproduct of the process.

So why spend any time with VBA at all when AI is all the rage and AI Agents will be the next wave?

Excel.

Excel Workbooks as Machines—And the Real (Operational) Work

First, what’s typically routine in a tax department?

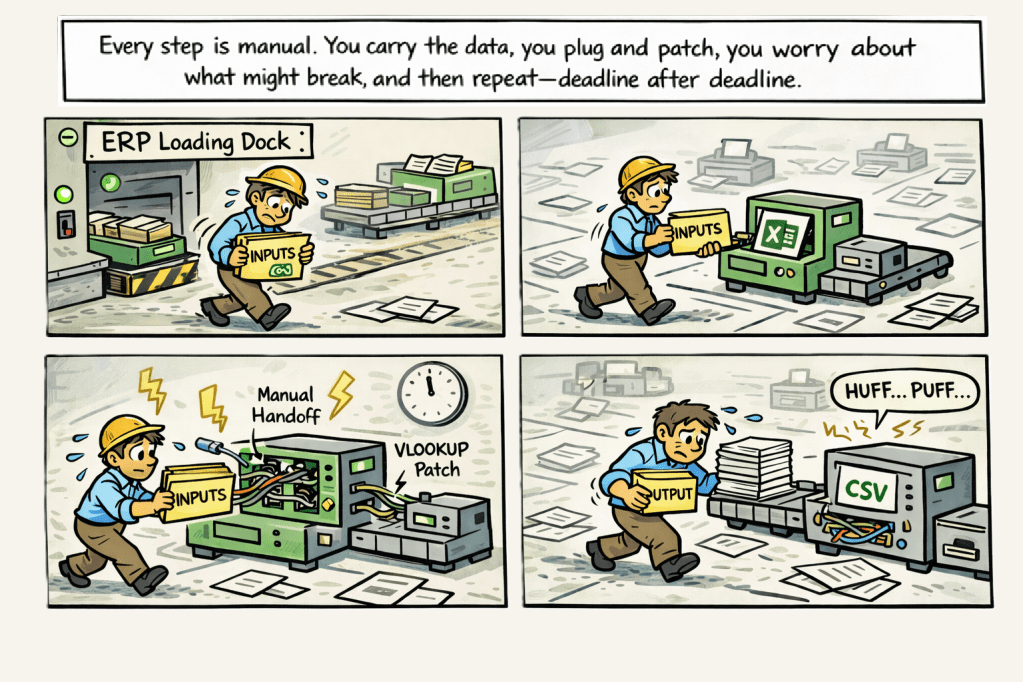

Deadline-driven, financial reporting and compliance cycles. Recurring calculations, reconciliations, rollforwards, data pulls, uploads, sign-offs, and fire drills.

These are “tax operations” (or “taxops”).

And all of it runs on Excel.

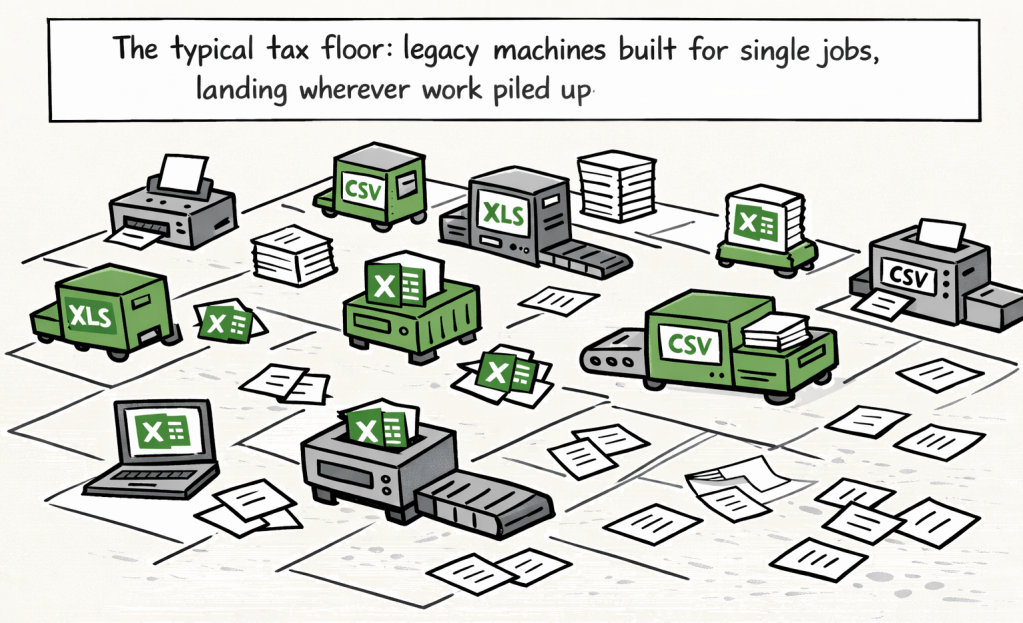

Excel is the chassis, the structural frame, for nearly all financial and tax data operations. Data may originate in ERPs, come from billing systems, or pass through specialized tax software, but it almost always lands in Excel. That’s where work actually gets performed; where we put the proverbial pen to the paper.

If you step back, you can see tax operations as a kind of factory floor. Each Excel workbook is a machine, engineered to perform a specific function, built on the chassis or frame that defines how your operations actually run.

The factory is digital, but the logic is physical: every workbook takes inputs, processes them, and produces outputs. Work moves from one machine to the next, and every copy/paste, manual adjustment, each re-link, or extra step is like carrying parts across the shop floor by hand instead of letting a conveyor belt do the job.

What New Architectures Make Possible

The activities in taxops are really the mechanical outcome of design choices many made years before. Many workbooks and workflows I built as a senior analyst were still in use when I left my role as the Head of Tax. I didn’t have a vision of “tax operations”; I hadn’t conceived that idea yet. And the team inherited those structures: built to deliver outputs, not to support an integrated floor plan.What’s always been missing isn’t good intent or effort, but the architecture – the deliberate layout and the real connective tissue both inside and between the machines.

That’s where VBA comes in. It’s the native language for architecting movement, coordination, and automation inside Excel – the chassis every operation runs on. For decades, VBA was out of reach for most accountants because it’s a programming language. But it’s 2026 now and AIs will write and explain the code; VBA is suddenly accessible. It can become the underlying “rails” or wiring that connects your factory machines, turning random workbooks into orchestrated workflows.

Example architectures:

Here are three styles of architectures that move you from a chaotic warehouse to a streamlined production line.

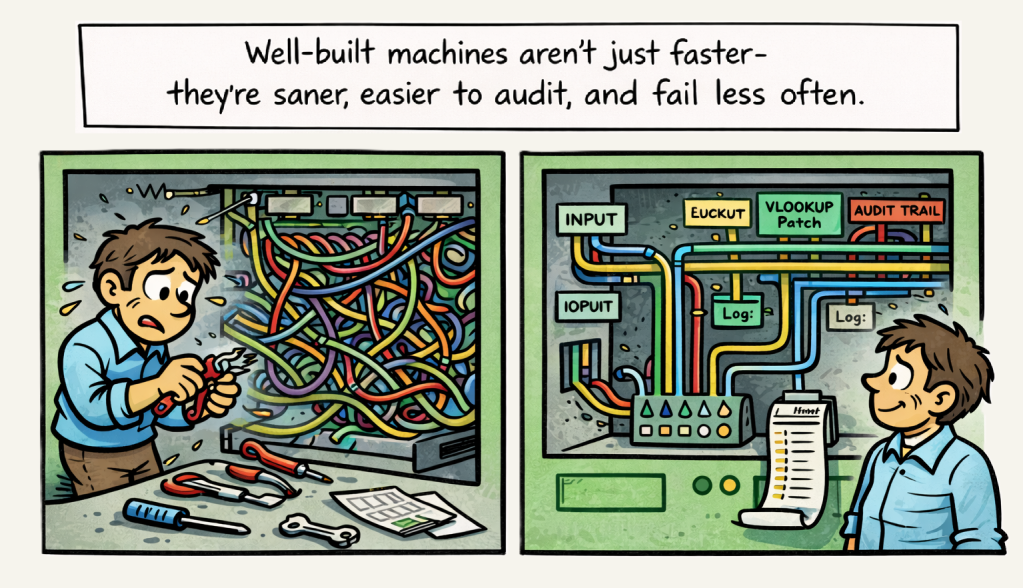

1. The Smart Machine: Robust Internal Architecture

Before you can connect machines, you have to make sure each one is built to last. A simple automation script is fragile; a well-architected machine is resilient. This means building in capabilities you’d expect from any professional software, right inside the Excel workbook.

Think of it like upgrading a machine with a proper control panel and a “black box” flight recorder. Instead of a simple script, a “smart machine” includes:

- A Governance Engine: It logs what was run, by whom, and when. It can even prevent a process from being run twice by accident, adding critical guardrails.

- An Environment Manager: It prepares the workbook for the task (like turning off screen updates to run faster) and resets everything if an error occurs. No more crashed files left in a broken state.

- A Dynamic Navigator: The workbook knows where it is on the network and can intelligently find the files and folders it needs. No more broken links when a folder is renamed.

You don’t need to know the technical details. Just know that this internal architecture is the difference between a brittle, one-trick macro and a reliable, auditable machine that can withstand the pressures of a real tax department.

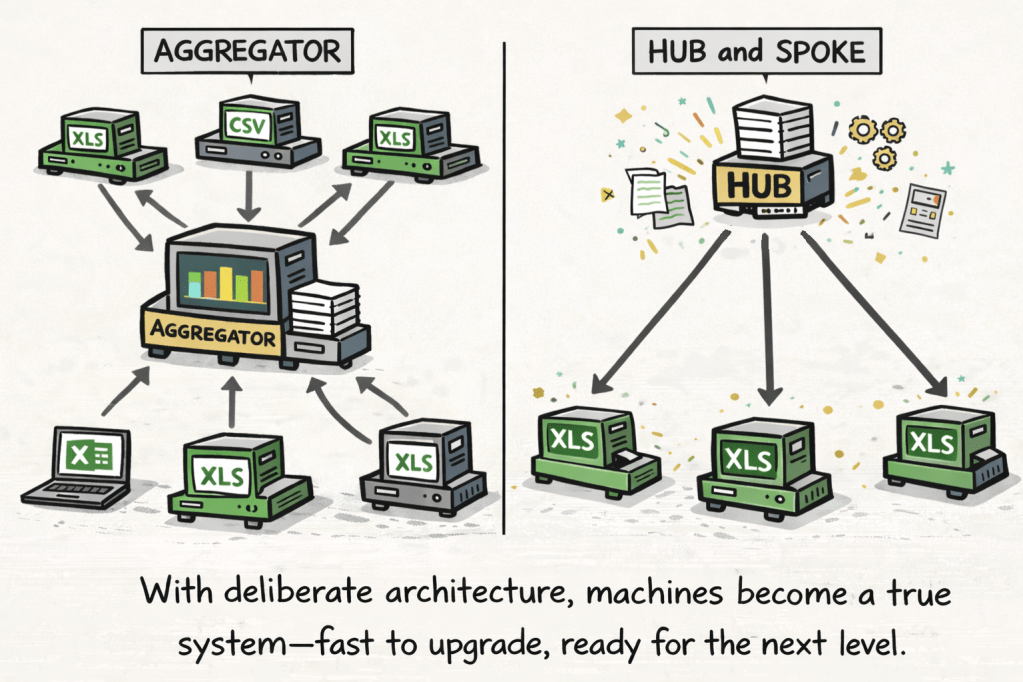

2. The Assembly Line: Chained & Aggregator Architectures

This is where you build the conveyor belts between machines.

- The Chain: This is your classic assembly line. The output of one workbook automatically becomes the input for the next. Imagine a process where your intercompany calculation workbook feeds its results directly into your EIFEL limitation model, which then produces a number for your compliance workbook that feeds a template to your compliance software. The data moves from one step to the next without anyone touching it.

- The Aggregator: This is for consolidation. One central workbook acts as a hub, automatically pulling in data from multiple other ‘machines’. Think of a quarterly provision process where workbooks from ten different divisions all feed their results into a single, consolidated model. The aggregator machine does the work of collecting and organizing, saving hours of manual copy-pasting and reducing the risk of error.

These architectures turn a series of manual tasks into a single, orchestrated workflow. You press one button, and the entire assembly line runs.

3. The Upgradeable Fleet: Hub-and-Spoke Architecture

What happens when you have the same “machine” (a standardized Excel template) deployed across dozens of divisions? Updating them one by one is a nightmare. This is where the hub-and-spoke model changes the game.

Think of it like a software update for your phone.

- The Hub: A central workbook where you store and maintain your standardized automation code.

- The Spokes: Your fleet of deployed template workbooks.

When you want to add a new feature or fix a bug, you update the code in the central hub. The next time someone work on the “spoke” workbook, you can easily pull in the latest version of the automation.

This architecture makes your Excel templates scalable and maintainable. You’re no longer just building individual machines; you’re managing an entire fleet of them, ensuring everyone is running on the latest, most efficient software.

VBA vs. Copilot: The Real Roles of AI in Excel Automation

So does AI actually fit in somewhere? It’s easy to assume that by 2026, Microsoft’s Copilot in Excel (or even the latest Claude add-in) would signal the end of manual work. They’re clever, helpful, and fluent within a worksheet. Need to write a formula, spot anomalies, summarize a tab, or add conditional formatting? Copilot can do it.

But step outside the boundaries of a single sheet, and the limitations show up fast. Copilots are “safe, they don’t touch the file system, can’t open or pull data from other workbooks across directories, and won’t trigger complex, cross-file processes. Their memory is painfully shallow, and their actions are, by design, non-destructive and sandboxed. They’re assistants for daily tasks, not system architects.

VBA, by contrast, is still the backbone. It’s the only way to reliably build “chassis rails” within and between workbooks. Its code is deterministic: set the rules and it runs the same way, every time. Only VBA can perform repetitive tasks predictably, and if engineered well, flex when deviations arise.

As of today, the real role for modern frontier AIs is in helping you write that VBA, debug it, and think through your system architecture but you must still be the process designer.

Put simply:

- Copilot is for when you’re at your desk, working inside the workbook, iterating and exploring.

- VBA (architected by AI) is for when you want the work done reliably, at scale, every time.

For tax operations – where accuracy, repeatability, auditability, and speed all matter – traditional automation with VBA remains the foundation.

Agents – Only ½ the solution

I’ve made assertions that “VBA is the backbone” and “VBA remains the foundation” without unpacking why these conclusions hold true now, and why they’ll matter even more in the era of agents.

The widespread executive hype around “rolling out agents” is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how they actually function.

All automation happens at the level of code.

LLMs, by contrast, operate at the level of language.

An AI agent’s job is to bridge that gap, we need to look at how that bridge is actually built.

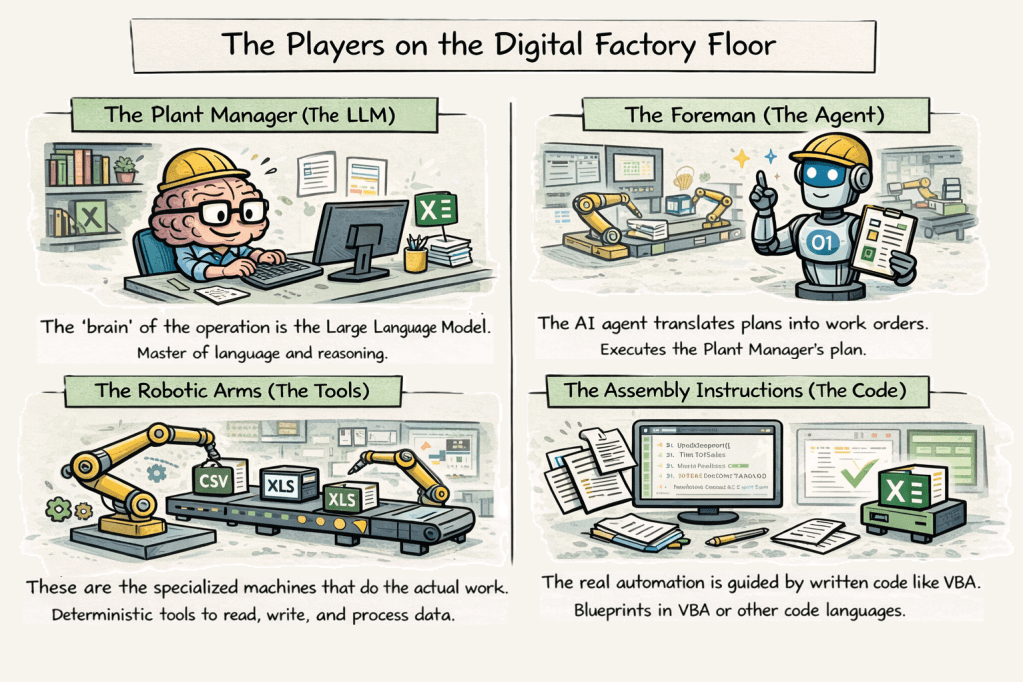

The Players on the Digital Factory Floor

To understand how agents work, and why your VBA matters, it helps to know the key players on this new digital factory floor. There are four distinct roles, each with a specific job.

The Plant Manager (The LLM) The “brain” of the operation is the Large Language Model. Think of it as a brilliant but creative Plant Manager. Its core skill is language and reasoning. You can give it a complex goal in plain English, and it can break that goal down into logical steps. However, it’s a master of language, not of doing. It can only talk about the work; it can’t operate the machinery.

The Foreman (The Agent) The AI agent is the Foreman who runs the floor. It takes the Plant Manager’s high-level plan and translates it into actual work orders. The Foreman’s job is a constant loop: observe the state of the factory, consult the Plant Manager for the next step, and then decide which tool to use to execute that step.

The Robotic Arms (The Tools) These are the specialized machines that do the actual work. Tools are deterministic functions the Foreman can call on. A file_reader tool reads a file. A script_executor runs a script. And a code_writer tool takes instructions and generates code. These tools are not intelligent; they just follow orders.

The Assembly Instructions (The Code) This is the most critical piece. The real automation that changes a file or moves data always happens at the code level. The instructions written in a language like VBA are the blueprints that the robotic arms follow.

The Agent’s First Day on the Job

Your new agent is dropped onto your tax department’s digital factory floor.

Scenario A: The Untamed Floor

The agent “looks around” and sees a maze of machines, ERPs, compliance software, and hundreds of Excel workbooks. Each Excel workbook is different. There are no maps, no instructions, just legacy workbooks with tangled formulas and undocumented processes. The agent has to figure everything out from scratch. It consults its “Plant Manager” (LLM), who tries to reason through the mess: “To reconcile these numbers, you’ll need to combine sheets from three different files. To roll forward this model, you’ll have to understand links that have changed names over the years.”

Every task becomes an investigation. The agent asks its “code writer” tool to generate one-off, untested VBA scripts, which adds variability. Execution is error-prone and slow. There’s no guarantee of the same result twice, and no reliable way to audit what happened.

This is simply a non-starter.

Scenario B: The Architected Floor

Here, the agent lands on a floor where each machine is clearly labeled and connected by well-maintained conveyor belts, your pre-built, validated VBA automations. The agent’s job is simple: read the existing blueprint, select the right script, and call on its toolkit to run that code.

Instead of guessing, the agent follows the process you’ve orchestrated: reliably, repeatably, and with a full audit trail. There’s no need to invent new instructions every time. The agent leverages what you’ve already built, ensuring every process runs as intended, and you can trust it when the stakes are high.

The Lesson: Just like your people, even the smartest AI foreman depends on the clarity and robustness of the systems it inherits. The more thoughtfully you architect your automations, the more powerful, repeatable, and auditable your digital factory becomes, for both humans and agents.

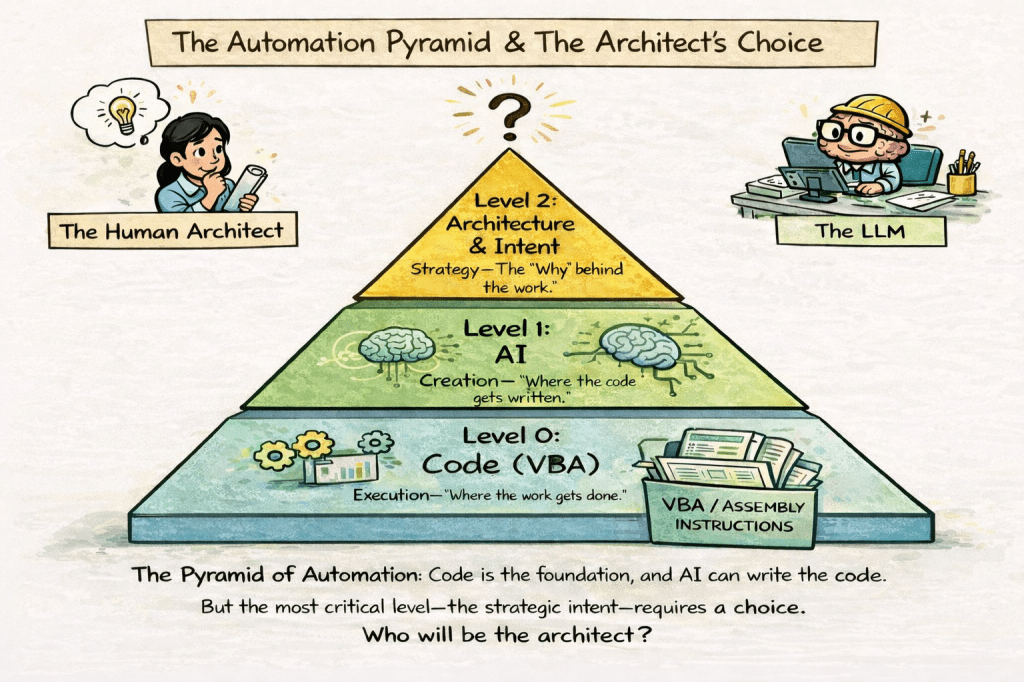

The Pyramid of Automation: Code, AI, and Intent

Step back and look at your operation from the ground up:

At the base, code runs the automation.

This is where real work happens. The instructions—written in VBA or another language—physically move data, reconcile numbers, create reports. Without code, nothing is automated.

A level up, code gets generated by AI.

The code writer (a tool powered by AI) can produce scripts better and faster than any human. But AI still needs to be told what to build, and how it should fit within the bigger picture.

Above both is the architecture and intent.

This is the blueprint, the “why”, the strategy that dictates which automations are needed, how they’re sequenced, who uses them, and what outcomes they support.

Here’s the only variable:

Who provides architectural direction, context, and intent? Do you leave your entire workflow design up to an LLM Plant Manager, or do you define it as the human strategist?

Where VBA Hits a Wall, and Where Agents Will Begin to Shine

VBA is an unmatched automation engine inside Excel. But the edges of most workflows extend far beyond a single workbook or the Office suite. Traditional automation platforms, like RPA or Power Automate, can bridge some of these gaps, but they typically require dedicated IT expertise, careful setup, and ongoing maintenance.

Agents promise to make this orchestration easier, more flexible, and accessible to domain experts, not just technologists.

In the coming wave, agents will make a real difference by:

- Orchestrating across applications, conversationally:

Agents will coordinate routines that span data from your ERP, trigger your Excel automations, and deliver outcomes to reporting or compliance systems via simple instructions. - Filling the last-mile gaps:

While traditional tools can move files or schedule automations, agents will be able to log into cloud portals (we’ll see how much CRA will allow this on My Business Accounts), pass outputs between platforms, trigger VBA from a chat, and close the loop with SOX review nudges and administration filing. Basically handling those little in-between steps that still slow everyone down. - Building and maintaining institutional knowledge:

Agents will help generate (and update) workflow documents, user guides, audit logs, and internal process documentation, turning tribal knowledge into shareable, evolving digital references, compounding efficiency and accuracy gains for subsequent runs by the agent(s).

There’s far more on the horizon: agents will eventually reshape how we handle knowledge, training, exception handling, and process adaptability itself. But all that’s beyond scope for today.

The Architect and the Factory Floor

So, why do I spend time orchestrating AI to build with a “dying language”?

Because for the foreseeable future, the most critical work in tax operations will run on code, and that code will live inside the Excel chassis. While agents will eventually handle the logistics between applications, they will rely on the robust, deterministic engines you build inside your workbooks to get the job done right.

Building those engines now is less a technical task and more an architectural one. With AI writing the code, your role shifts from being the worker on the factory floor to being the chief engineer who designs it. The AI provides the syntax.

No real-world factory would tolerate endless manual rewiring or hand-carrying parts from one machine to the next. It’s time we stop accepting it in our digital operations. Start by seeing your workbooks as machines, identify your first missing conveyor belt, and begin designing a factory floor that is built for tomorrow, today.

I’m here for you, and guarantee you’ll get time back into your day for the more interesting work, when the boring stuff is running on rails!